I was recently in a social situation when I saw a woman lingering near the group that I was loosely connected with. She was holding a vogue-like non-smile on her lips. Her makeup was perfect over her young skin. She said nothing to anyone.

We were five feet apart when my line of vision and hers clicked like two LEGO bricks, so I smiled and said, “Hi, my name is Linda.”

“We’ve met like ten times before!” She snarled at me, gave her head a short shake in disgust, and casually sauntered away.

And this is my darkest worry of how the world is really thinking about my ability to remember details.

Indeed, once she pointed out our prior meetings – and I don’t think there had been ten – I remembered a conversation with her from months ago; again, I had introduced myself to her. That time she said we had met before and then we briefly discussed hair color and style as probable reasons I didn’t recognize her. She wasn’t wholly impressed with me then either.

When I meet new people in a crowd, I always say with a laugh that I will probably ask them their name again in the future. Whether being truthful or being politically correct, inevitably, they laugh and say they will most likely do the same.

The sting of the words and the tone coming from that perfectly made up face have stuck with me for days. I know this is not a person I need in my camp, yet my initial thought pattern puts me in a spot of guilt that I made this person, this sensitive woman, feel bad by not remembering her name. That guilt doesn’t last when I rationalize it for twenty seconds: this isn’t how I would treat anyone who had just introduced themselves to me. And this particular person is not sensitive.

I think I know enough from that encounter that a warning bell will chime in my head should I see her again, and that will remind me to leave out the introduction with my greeting. And, you darn right, I’m going to smile and say “hello.” However, I’m still sorting out why I feel even slightly compelled to say “hello.”

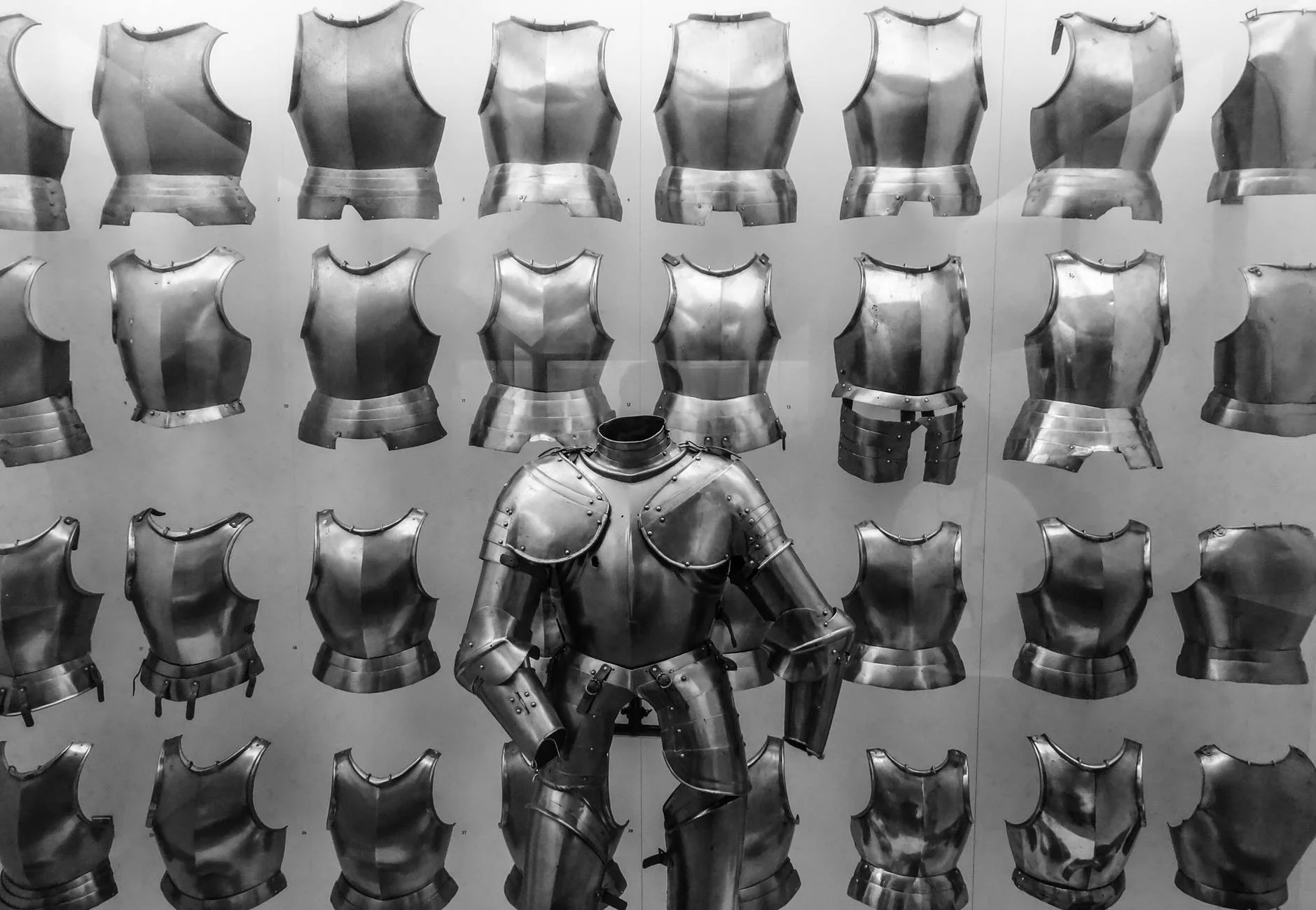

Years ago when Will was very young, he wanted to play baseball in the spring, but his gymnastics coach frowned on that, despite the fact that the competitive season had ended. Will was struggling with what to do. He respected his coach and didn’t want to let him down. I said, “Do you want to play baseball?” He nodded. “You’re ten, you can play baseball,” I told him. I knew that didn’t make the decision any easier, so I continued. “Will, your coach wants you at gymnastics practice because he’s the gymnastics coach, but you need to make your own decision because you’re ten and you want to play baseball. And, you need to put a fence around your heart and not let his words affect your decision. There will be times in your life when you need to keep your heart safe behind that fence – and this is one of them.”

That was a great moment for me. Not a great Mom-moment, but a Linda-moment. I’m not sure Will even remembers the conversation, but verbalizing that sentiment has been a useful reminder for me ever since Will played in Little League that spring. Sometimes you need a rational, armored fence such that every pinging sting doesn’t hit your heart.

“We’ve met like ten times before!” found a breach in my breast plate.

I’ll say “hi” again, for I know no other way to mend that imperfection in my armor. And, because Mom has always said, “Kill them with kindness.” I learned last summer that the action of killing-with-kindness can be maneuvered with either a passion for putting kindness into the world despite the situation or with the precision of sliding a thin metal blade into the toughest leather. I prefer the first, but I rather inadvertently resorted to the latter last summer.

A young man from the East Coast sat down next to me in a writing class. We introduced ourselves to one another, and when he heard that I was originally from Iowa, he rolled his eyes and groaned. He said something to the effect that his writing may upset me because the topic of the ten-page submission was how he more-or-less despises Midwestern kindness. He was familiar with this phenomenon first-hand as he had accepted the most economical master’s program offered to him – and it happened to be in the Midwest, in the middle of cornfields. God’s country or God-forbidden country. His upfront nature was refreshing; sometimes I appreciate this directness in people. He spoke of the topic in a third-person removed sort of way.

As the week went on, we talked very little; still I could feel that he was exasperated by most people and most situations. In class on Friday, he said he was looking forward to hiking that evening and exploring the area. When I saw him Saturday morning, his arm was in a cast. For the next week, he needed help from strangers – including one Midwesterner.

Sunday afternoon, he asked me for a ride to pick up x-rays from a clinic and medicine from the pharmacy. I smiled. And, said I would. I hadn’t read his submission yet as he wasn’t scheduled for review until the last day of the two-week course, so I hadn’t seen his thoughts on Midwesterners in black and white. Honestly, I may have subconsciously decided it wasn’t one I needed to read, period.

He thanked me profusely for being so kind as to drive him around for two hours. I responded something to the effect of you need help and I have the time and the transportation. We went to the pharmacy first, but his meds weren’t ready, so we decided to pick up the x-rays first.

Three times I had to ask him what the address was of the clinic. The third response was finally audible: Love Avenue. I openly grinned as I gave him a knowing look. The universe was speaking loudly. It would have been impossible for either of us not to acknowledge how painful it was for him to be chauffeured around town by a woman from Iowa, let alone having to ask her for a ride to Love Avenue.

This man was a forthright contrarian writer. And a contrarian in life. No matter what me, a Midwestern optimist, might say, he would have the exact opposite response. Nothing would give him a glimmer of light to put a little cheer in his demeanor. I accepted that. He accepted the ride. He left campus early. I never read his paper.

I can’t remember his name now, but I still wish him well from afar. Perhaps our opposing outlooks will neutralize one another, throwing less yuck at the general human condition.

So, yes. Next time I see the woman whose comment I remember but whose name still escapes me, I will smile and say hello. She might need that smile – and it’s no skin off my back. Nor is her comment now that I’ve thoroughly let my fingers think about it. Her retort was not about me but rather something within her universe.

I had a thought this morning about my memory. Ever since chemo and with being on hormone suppressants for a decade, my memory has suffered – but my hair has become extremely curly. I think my memory is leaking through my hair follicles and putting kinks in my locks.

It makes me smile to think that I might know where my memory resides nowadays.